Henry Ford & Hitler: A Dark Industrial Alliance

Henry Ford and Adolf Hitler were bound by a jarring historical paradox that loomed large in the austere corridors of power in Munich. Within the private sanctum of the Nazi Party headquarters, above the desk where Hitler drafted blueprints for global domination, hung a carefully framed portrait of Ford—the American icon who put the world on wheels. This image was no mere ornament; it symbolized a complex material and intellectual entanglement that would haunt history, connecting the ingenuity of Detroit with the madness of Berlin.

When Henry Ford ideas crossed the ocean and reached the heart of Nazism

Scattered across the coffee table near Adolf Hitler’s desk were copies of The International Jew, a compilation of incendiary articles previously published in Ford’s own newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. This detail might have been trivial had the author been a marginal figure. But the fact that the author was Ford himself—the pride of American industry—drove researchers to excavate this disturbing relationship deep. In the mid-1990s, lawyers representing Holocaust victims seized upon these details, seeking to establish the moral and legal liability of the Ford Motor Company for its potential role in lubricating the Nazi machine.

The admiration was far from unilateral. The Washington Post cited historical sources indicating that two years before becoming Chancellor, Hitler told a Detroit News reporter plainly: “I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration.” This wasn’t merely industrial inspiration; it bled into political and racial ideology. In 1923, Hitler was quoted describing Ford as the leader of the growing fascist movement in America, expressing open admiration for Ford’s anti-Semitic policies, which aligned seamlessly with the Bavarian fascist program. Hitler even went so far as to wish he could deploy “shock troops” to major American cities to support a potential Ford presidential bid.

It seems the stuff of fiction. How could the embodiment of the American Dream—a man who helped build the middle class and revolutionize the global economy—serve as a muse for history’s most bloodstained dictator? How did a simple farmer’s son command such acknowledgment of greatness from the “Führer”? To answer this, we must turn back the clock to the muddy fields where great dreams were born.

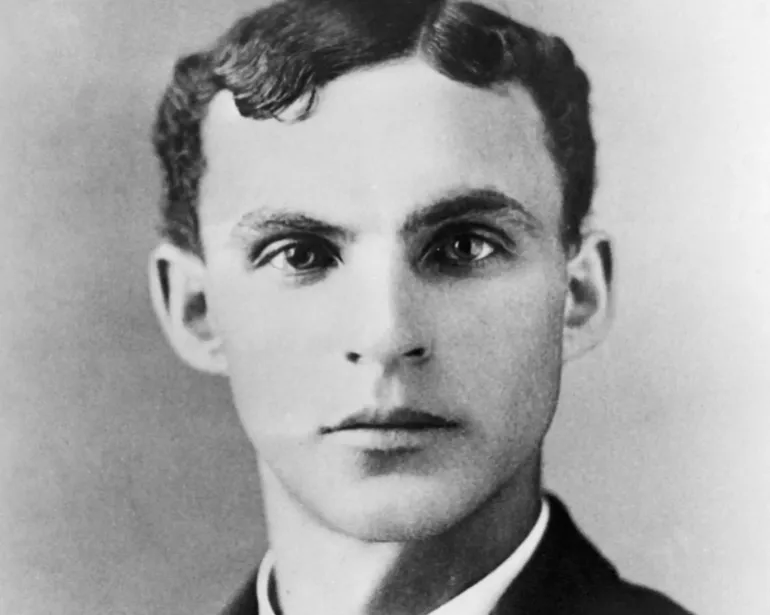

Born in 1863 on a farm near Dearborn, Michigan, Henry Ford’s family was not destitute, but they lived a life of subsistence and arduous labor. In his autobiography, My Life and Work, Ford recalls those years with a bitterness tempered by defiance, describing farm labor as harsh and inefficient. From an early age, he was driven by a conviction that better, more efficient methods had to exist. While other children played with store-bought toys, Ford built his own from scrap metal, treating every piece of machinery as a discovery. He had little patience for traditional academia or elite professions; his true calling was mechanics—an idea rooted in the belief that technology could serve humanity and relieve the weight of relentless labor. This formative period, and its broader historical implications, is also examined from an Arabic cultural perspective on السهول.

The great turning point occurred when he was twelve—an event he later described as the biggest moment of his early years. It was on a road outside Detroit that he crossed paths with a massive, self-propelled steam engine. It was the first vehicle he had ever seen moving under its own power, without horses. It was a crude, hulking machine meant for plowing, but the chain connecting the engine to the rear wheels captivated the boy’s imagination. It was the spark that ignited his entry into the world of mechanical transport.

By thirteen, he was an expert watch repairman, a skill demanding immense patience and precision. His father intended for him to inherit the farm, but Henry saw his future in gears and oil, not plows and soil. At seventeen, he made the fateful decision to leave school for a machine shop, finding his calling in exacting work. Though he briefly considered manufacturing cheap, popular watches, he abandoned the idea upon realizing a fundamental economic truth: watches were not a universal necessity. He was searching for something bigger, something essential that would replace the horse and reshape the landscape.

His journey was paved with practical education and failures. He worked with large steam engines at Westinghouse, learning their limitations—they were too heavy and expensive for the average farmer. He needed something lighter. The revelation came via a British magazine article about the “silent Otto gas engine.” In 1885, the chance to repair one of these rare engines gave him the insight he needed. By 1896, back on his father’s farm—ostensibly settled down, but secretly experimenting in a workshop—he built his first car, the “Quadricycle.”

It was a noisy “nuisance” to the public, terrifying horses and drawing crowds whenever it stalled. Ford had to chain it to lampposts to prevent tampering and eventually became the first driver in America to require a special police permit. Yet, the merchant’s mindset was forming; he sold that first vehicle for $200 to fund a lighter, better successor.

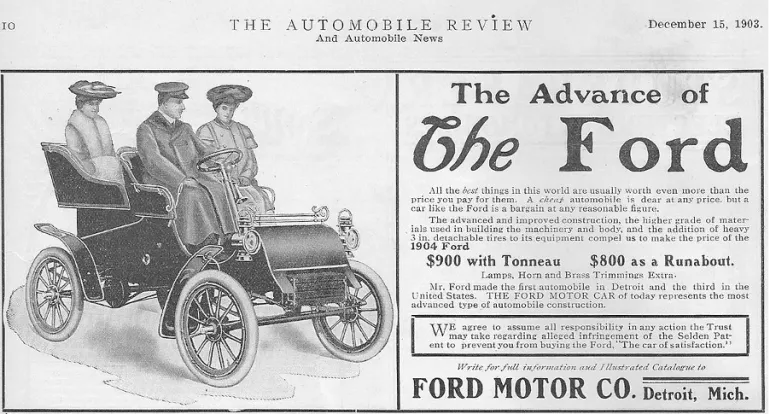

Early commercial ventures were rocky. He resigned from his first major outfit (which later became Cadillac) in 1902, determined never to work under another’s command. In 1903, the Ford Motor Company was born, and with it, a new industrial philosophy. Ford maneuvered for total control, buying out shareholders until his family owned the company outright by 1919. His vision was singular: a simple, safe, universal car for the masses. This materialized as the legendary Model T.

While automobiles were playthings for the rich, Ford shattered the paradigm. He relentlessly lowered prices to boost sales—from $825 in 1908 to a mere $290 by 1924. This magical deflation was made possible by the introduction of the moving assembly line in 1913, inspired by Taylorist principles of scientific management. Instead of workers swarming a stationary chassis, the work came to them, boosting productivity astronomically. By 1921, Ford commanded 61% of the American market, transforming from an obscure mechanic into a living legend. Yet, this immense fame attracted a dark admirer across the ocean, initiating the most controversial chapters of his life.

Decades later, in the late 1990s, the ghosts of World War II returned to Dearborn. Lawyers scrutinized corporate archives, revealing that American industrial giants, including Ford and GM, had played a dual role. While they marketed themselves as the “Arsenal of Democracy,” documents revealed they had also functioned as an “Arsenal of Fascism.” By 1939, their German subsidiaries controlled nearly 70% of the German auto market. Ford’s German branch, Ford-Werke, became the second-largest producer of trucks for the Nazi army, vital for transporting troops and materiel.

The relationship went deeper than mere business compliance under duress. Reports suggested bartering deals that provided the Reich with strategic raw materials like rubber. Ford’s personal views cast a long shadow; he initially opposed US entry into the war and, in 1940, personally vetoed a US government-approved plan to build Rolls-Royce aircraft engines for the beleaguered British Royal Air Force. This symbiosis culminated in July 1938, when Henry Ford accepted the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest Nazi honor for a foreigner—a symbolic welding of industrial genius and ideological madness.

But the connection was rooted in more than machinery; it was spun from words of hate. throughout the 1920s, via his newspaper The Dearborn Independent, Ford disseminated virulent anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, later collected in the book The International Jew. These writings crossed the Atlantic and found a receptive disciple in Adolf Hitler. In Mein Kampf, Hitler praised Ford as the lone “great man” maintaining independence against the supposed Jewish threat. The automaker had become a prophet for the ideology that would later incinerate Europe.

However, the backlash in America was severe. Facing boycotts and lawsuits—and a clever threat from Hollywood moguls to use Ford cars exclusively in crash scenes in movies—the pragmatic businessman retreated. In 1927, he closed the newspaper, withdrew the books, and issued a humiliating public apology to the Jewish people.

Henry Ford died in 1947, leaving behind a profoundly dualistic legacy. He was the genius who liberated humanity from the constraints of distance, created the middle class, and founded modern manufacturing. Yet, he remains a man whose ideas stained history, and whose factories helped power one of the most brutal regimes mankind has ever known. It is a stark reminder that genius in industry offers no immunity against catastrophic moral failure.